Ultrasound capsules

Introduction to regurgitation

Valve farts?

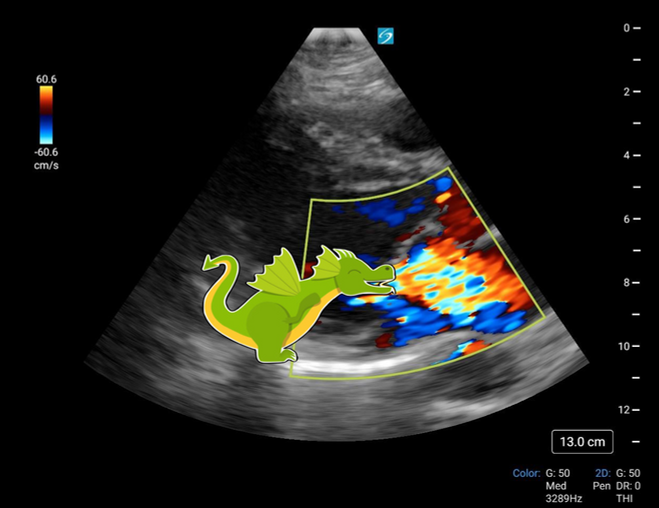

Dragon breath?

No matter what image you use to describe regurgitation, this page will attempt to shed some light on the basics and introduce you to the search for (severe) regurgitation.

So... what do we look for when evaluating valves for regurgitation?

Qualitatively

Coaptation

Excursion

Mass/deformation

Coloratively

Color Doppler farts/jets from the valve to the previous chamber.

Quantitatively

Too much pushing! Let's forget about that for now.

Finally, we will discuss the criteria for suspecting severe regurgitation (and therefore impacting management!)

Qualitative assessment

#1: Coaptation

Coaptation is assessed when the valve closes. Do the leaflets fit against each other adequately? In theory, if the answer is yes, this means that the valve is airtight and therefore there is no regurgitation. Conversely, if the leaflets do not coapt well, regurgitation is guaranteed. A lack of coaptation is not necessarily a sign of pure valvular pathology... dilation (LV, aortic root) can lead to a loss of coaptation secondarily. Unfortunately, this qualitative assessment only allows us to detect major coaptation defects. Our eye will miss the more subtle ones...

#2: Excursion

This is more useful in assessing stenosis. In fact, limited movement --> limited opening --> stenosis. However, abnormal excursion indicates valvular disease and therefore increases the likelihood of regurgitation.

#3: Structural abnormalities/masses/endocarditis...

Leaflet assessment can lead to surprising discoveries! Masses and vegetations easily visible on TTE are rare... but their identification should lead to the suspicion of regurgitation. Indeed, any structural change will cause a loss of patency and therefore regurgitation. Endocarditis can also "eat away" at the valve and create microperforations that will lead to regurgitation of varying degrees.

#4: Acute or chronic?

One factor that can help determine the chronicity of valvular disease is the assessment of the chamber receiving the regurgitation. Indeed, chronic significant mitral regurgitation will cause LA dilation. Along the same lines, chronic significant IAo can lead to left ventricular dilation or LVH.

However, the causes of acute valvulopathy are rare. Trauma, heart attack with rupture of a mitral pillar, aortic dissection, endocarditis... These are conditions where patients will present to the emergency room quite ill. Rarely are waiting room patients (although)... The clinical aspect must always prevail!

Color Doppler Assessment

Color Doppler Evaluation — The Core of Regurgitation Assessment

-

The color Doppler truly is the key tool when assessing valvular regurgitations.

What is a color Doppler?

-

It’s a tool that allows you to evaluate the movement, direction, and velocity of a fluid within a defined area.

How to interpret a color Doppler:

-

When you activate color Doppler, a box appears on one side of the screen. --------------------->

It indicates:

-

The color of flow moving toward the probe (red in the example shown) and the flow moving away from the probe (blue).

-

The velocity of the flow as estimated by the machine.

-

In cardiac ultrasound, we generally aim for a range of +70 to -70 cm/s, with a maximum of ±50 cm/s.

-

-

A flow that is too fast for the set scale will produce what’s called aliasing — basically, it will look like a color storm that’s difficult to interpret.

Optimizing color Doppler:

-

First, optimize your 2D image!

A poor-quality 2D image won’t magically improve with color Doppler. -

Properly position the Doppler evaluation box.

-

It should cover the regurgitant chamber, the valve, and a bit beyond.

(Example: the left atrium, mitral valve, and slightly more)

-

-

Be cautious not to assess too large an area — the information becomes mixed, and the machine’s analysis becomes overloaded and less accurate.

-

Color Doppler works best when the flow is parallel to the probe → therefore, apical views (4-, 5-, 2-, and 3-chamber) are best for assessing mitral or aortic regurgitation.

-

The parasternal long-axis (PLAX) view remains excellent for screening severe aortic or mitral regurgitations, as it provides clear visualization of both the aortic and mitral valves along with their respective regurgitant chambers (LV outflow tract and LA).

-

Patients with acute regurgitation are often very sick. Using FREEZE and scrolling through the clip to evaluate the jet during the correct cardiac phase (systole or diastole) can be very helpful!

What does regurgitation look like?

One of my residents described it as a dragon’s fire breath, and I love that analogy!

For those less familiar with dragons and princesses, imagine an explosive bout of diarrhea in Mexico — also a pretty vivid image.

I’ll let you choose which one you prefer.

A regurgitant jet typically starts small at the valve, then widens in a roughly triangular shape, forming the classic appearance.

That said, atypical jets do exist:

-

Eccentric jets, which follow along the border of a structure (often curling along the atrial wall).

-

Diffuse jets, where the valve is essentially perforated or “sieve-like,” allowing a massive and widespread regurgitant flow.

Severity Assessment

Since this is only an introduction after all, we will focus on one criterion... the % of volume occupied by regurgitation.

% of the OG occupied by a mitral regurgitation jet

% of the LV outflow chamber for an aortic regurgitation jet.

And after all, I see 4 main scenarios where identifying regurgitation can significantly change PEC.

Syncope

Suspected endocarditis

Suspected aortic dissection

Very sick pt with murmur (shock and/or respiratory distress mainly)... and for regurgitation to result in moribund state, it has to be SEVERE. So... what % is synonymous with severe MI or AIo?

For an MI: 40% of the LA volume occupied OR an eccentric jet that swirls OR a jet that hits the posterior wall of the atrium.

For an IAo: 60% of the volume of the flushing chamber.

For the rest, it is simply non-severe IM or AIo.

Other examples:

Here, we have the same patient in PSL vs. in A4. The A4 allows us to demonstrate a mild IAo missed in PSL but above all to better assess the severity of the MI.